America Needs Historians

The discipline of History is above all a quest for understanding: when human beings understand why the world is the way it is today, it helps us plan for and shape the future. Here are some examples.

1. Ukraine

Ukraine had its start as a state when Scandinavian warriors and merchants created Kievan Rus’ in the ninth century; from the beginning, it was multi-ethnic, with elements of Scandinavian and Scandinavian culture (plus other groups like the Pechenegs and Khazars) sometimes fighting and sometimes cooperating with each other. It held together as a state until the great Mongol expansion of the thirteenth century. Some territories gradually broke free of Mongol control, much of the west falling under the sway of Lithuania, Poland, or Hungary.

The turn toward Russia came in the mid-seventeenth century, when the leaders of a great Cossack rebellion in Ukraine chose to ally with Muscovy. Over the next century, the expanding Russian Empire took over much of the agriculturally desirable and well-situated territory, but the west of Ukraine became part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. When the Russian Revolution came in 1917, parts of Ukraine tried to go independent, while the leaders of other regions eagerly accepted a role as part of the Soviet Union. Soviet rule gradually became less benign, however, including a vigorous policy of “Russification”—eliminating the Ukrainian language and culture in favor of that of Russia—and a man-made (perhaps purposefully) famine that killed 4–5 million Ukrainians. In WWII Ukraine suffered brutal occupation by both German and Soviet troops. Ukraine was able to declare its independence in 1991, with the breakup of the USSR.

But, like most historical issues that have developed over centuries, it’s complicated. Many people especially in eastern Ukraine identify more with Russian culture; those in the west, thanks to centuries of rule and interaction, look to Europe. It’s a multi-historied and multi-cultural state. History is complicated, and issues are rarely as black-and-white as news coverage or political speechifying makes them sound. History can help us understand the world and the issues we live with today.

Consider a history major or minor2. How Hitler Came to Power

How did Adolf Hitler come to power in Germany? It’s a complex story that includes bad political decisions (by Germans and others), real hardship in Germany, and a lot of fear-mongering. History has lessons to teach, but usually the essential truths lie in the details. History very rarely simply repeats itself (although historians do!) but, as Mark Twain said, it often rhymes.

How did Adolf Hitler come to power in Germany? It’s a complex story that includes bad political decisions (by Germans and others), real hardship in Germany, and a lot of fear-mongering. History has lessons to teach, but usually the essential truths lie in the details. History very rarely simply repeats itself (although historians do!) but, as Mark Twain said, it often rhymes.

After his valiant service in WWI, Hitler was a man with a mission. Like many, probably most Germans, he felt betrayed by the criminalization of Germany embedded in the Treaty of Versailles that ended the war, with its massive demands for reparations. To Hitler’s mind, what was needed to pull the defeated, impoverished country together again was a return to traditional and German values. That meant an attack on foreign ideologies (most notably Communism), “immoral” behavior (such as homosexuality), and alien foreigners embedded in the Fatherland (the Roma and of course Jews, who were also suspected of being pro-Communist). Hitler soon allied with the most violent elements demanding the “purification” of Germany, and in 1921 became leader of the young National Democratic Socialist Workers’ Party (the Nazis). In 1923 the Nazis boldly attempted a coup; it failed and Hitler was imprisoned, although popular agitation limited his term to a single year. After his release, the Nazi leader grew ever more strident in his demands for change. An astonishingly charismatic speaker (listen to one of his speeches sometime!), Hitler’s message fell on receptive ears. Germany was suffering both in its pride and in the grip of a massive economic depression; it’s easy to look for scapegoats under those circumstances.

At the start of 1933 President Hindenburg named Adolf Hitler as chancellor. It’s an office like that of prime minister in the UK—the party that wins the largest number of seats in a parliamentary election is invited to try to form a coalition government. The Nazis hadn’t gotten the majority of seats, but they were the most successful party. Exactly four weeks after Hitler became chancellor, in February 1933 a hysterically fear-inducing event occurred: the house of parliament (Reichstag) was destroyed in an arson fire (under rather mysterious circumstances). The communists were accused of the deed, and a state of emergency was declared that suspended civil liberties in face of the (largely imagined) threat. Soon thereafter, Hitler’s propaganda machine had so worked up public terror that President Hindenburg was convinced to agree to the Enabling Act of 1933, giving Chancellor Hitler the power to make and enforce laws without the Reichstag or the president. This overriding of the checks and balances built into Germany’s constitution allowed Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party to consolidate their hold on Germany, with devastating consequences for both their homeland and the world.

Consider a history major or minor3. Bravest of the Brave

The most highly-decorated military unit in U.S. history is the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, recruited and trained in 1943 and sent to fight in the European theatre of World War II in 1944 and 1945. This unit served with outstanding skill and bravery. More than 4000 Purple Hearts and 4000 Bronze Stars were awarded to its soldiers, and no fewer than 21 of its members received the Medal of Honor.

One of the combat team’s most impressive feats was the rescue of the “Lost Battalion”—a force that had been trapped behind German lines in France in October 1944. Conditions were appalling. The trapped battalion was dug in but were mostly out of ammunition (more could not be airlifted in because of dense fog). The 442nd fought its way through the German force encircling their comrades in arms in massively heavy fighting through dense fog, rain, and even snow. They finally forced the Germans back when men of the 442nd charged the German positions lobbing grenades.

Oh, and an important thing to know about the 442nd Regimental Combat Team: the unit consisted mostly of Japanese Americans. They had been recruited in part from the large Japanese population of Hawaii and the rest from the internment camps where they and their families had been imprisoned during the war. They were American citizens, mostly second-generation residents of the country. What inspired these men to fight so valiantly for a country that had done them such harm?

It took a long time for the 442nd’s contribution to receive full recognition. In 2011 the survivors of the unit were presented with the Nisei Soldiers of World War II Congressional Gold Medal; in 2012 the remaining veterans were made chevaliers of the French Légion d’Honneur for their role in the liberation of France.

History explores both the big picture and the role of individuals in the past. Historians have a pesky habit of adding nuance and struggling to understand causation and effects, often uncovering stories that have been forgotten but deserve to be remembered.

Consider a history major or minor4. Really? A race named for an athlete who overdid?

Marathon races take their name from the Battle of Marathon in 490 BCE, when an Athenian army defeated an invading Persian force. A runner named Pheidippides took the news the 28 miles (the person who designed the modern race mistakenly calculated the distance from the modern village of Marathona, not the battle site) to Athens, gasped out his news of the victory, and died. Seriously—this guy got a race named in his honor?

Marathon races take their name from the Battle of Marathon in 490 BCE, when an Athenian army defeated an invading Persian force. A runner named Pheidippides took the news the 28 miles (the person who designed the modern race mistakenly calculated the distance from the modern village of Marathona, not the battle site) to Athens, gasped out his news of the victory, and died. Seriously—this guy got a race named in his honor?

If that’s all the further you look into the matter, you’ve missed out on a story of great courage and endurance, a tale that makes both the battle and Pheidippides’ great run worthy of commemoration. Studying history can give warnings, expose dark deeds, and entertain—but it can also inspire. This is what happened at Marathon.

Persia, the superpower of the age, was set to teach the small Greek city-state of Athens a lesson (the Athenians really shouldn’t have supported a rebellion against the Persian king). A large fleet carried an invasion force to Greece, making landfall near Marathon. The force significantly outnumbered the Athenian army, and was especially dangerous because of the large number of cavalry (the Athenian army was completely infantry). Athens had sent the runner Pheidippides the 150- mile round trip to Sparta begging for assistance, only to be told the Spartans couldn’t come yet. So the entire Athenian army marched to Marathon to block the Persians from their city, leaving nobody to man the walls of Athens itself.

After a several-day standoff, the Persian commander hatched a scheme. He left the bulk of his army to pin down the Athenian force, but set sail to take and destroy the undefended city. The Athenian commander, realizing what was happening, forced the battle—it was the first time Greek infantry had ever marched at the double, to get across the open ground where the cavalry was effective. And the well-armed and very well-motivated Athenians won the day.

That, however, was not the end of the matter. The Athenian fighters had to get word to the city that they had won, lest the despairing city officials open the gates to the invaders coming by sea. So Pheidippides, who may well have just fought in the Battle of Marathon, was sent with the news. He was a professional distance runner and must have known the toll the run was taking on his body (much of it is uphill, by the way), but speed was of the essence. He succeeded in delivering his message—that the Athenian army was victorious and that the whole force was marching back to defend the city as quickly as they could. He died . . . and in the event the Athenian army got home a few minutes before the Persian fleet arrived. But Pheidippides could not have known that. History really can inspire.

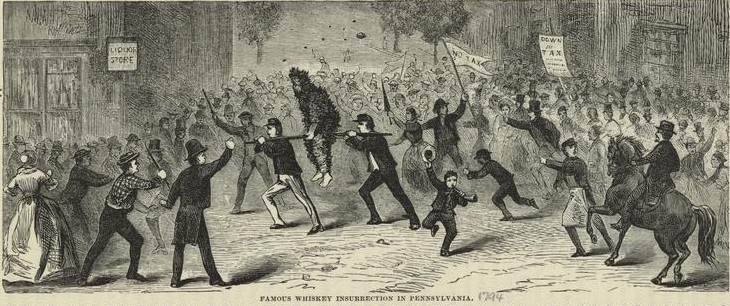

Consider a history major or minor5. The Whiskey Rebellion

In the western frontier lands (we’re still well east of the Mississippi in this period) farmers who normally distilled their own whiskey with surplus grain bitterly resented the law. They rapidly turned to violence, assaulting tax collectors, doing really nasty things like tarring and feathering them. Things came to a head in July 1794 when a band of at least 500 men in western Pennsylvania attacked a U.S. Marshal’s fortified home.

President George Washington sent negotiators—but he also called on the governors of nearby states to mobilize their militias to put down the insurrection. Then the president himself led the 13,000 militiamen who were contributed from four states against the rebels. The rebel leaders fled as the federal army approached, so there was never a battle. About 150 people were arrested, but only 20 put on trial. Only two were convicted, and even they were later pardoned.

What’s the lesson? Besides “never get between a man and his whiskey,” of course. The tale of the rebellion was the first serious test of the whole notion of a federal government, as officials and citizens alike worked out what the boundaries were between federal, state, and individual rights. It is certain that the United States could not long have endured if Washington had backed down. But the Whiskey Rebellion is also a beautiful example of sound statesmanship. President Washington had to take a stand against the rebels for the union to survive, although he continued to seek a peaceful solution even when matters had come to a head. After the point had been made, however—that the federal government was the law of the land—he focused on reconciliation and easing tensions rather than on punishment. The United States was the stronger for George Washington’s actions. Can events that happened more than 200 years ago help instruct us on how to behave today? Of course they can. . . as long as we know about them.

Consider a history major or minor